Roastmaster's Blog

Thanks

The winds have shifted from south to north and the temperature has gone from unbearably hot to unpredictably mild. The leaves on my October Glory maple got stuck in that half-red, half-green phase that is so brief, streaked with the colors of Christmas I remember from my childhood, remarkable in its natural vividness. In Spanish-speaking coffee lands, this is called “pintón,” when the coffee cherries are ripening on the thin, resilient limbs of their mother tree, reddening from the woody attachment but still green at the tip; coffee that tastes less sweet than the fully ripe, “maduro” coffee we’ve grown to love, the coffee that has completed its chrysalis.

Life is always in flux, and fragile. Our best laid plans shift slowly, and suddenly. Ideas become stubborn and then break like a green stick, or they evolve as our cells rearrange and turn our hair an elderly grey. I think back about the big changes in my life, and none of them happened like I thought they would. The idea that my dad would die and my cat would die seemed as unrealistic as the idea that I could die. I think about my temptation to change the name of the DoubleShot, when the pervasive lawyers for Starbucks threatened, compromised with the demand that I put a space between Double(and)Shot, and I resisted. I refused. And in that case it’s the space that doesn’t exist that indicates that the DoubleShot name inherently stands for justice and right and standing up for what we believe in. But we change. It has always been our mission to source and serve the best coffee that we know how, to as many people as we can. And that means amending our methods, altering the product, shifting our mindset about what excellent coffee means (but not deviating from our purpose). After all, it’s change that takes coffee from a seed planted in the tropical mountain soil, transformed through the flames of my roaster, and extracted by the worlds wealthiest solvent.

The biggest change for the DoubleShot that happened over the course of the last few years culminated with the completion of The Rookery. We moved overnight in March from our strip on Boston, leaving the cold cinder block walls that were only warmed by the people within. The intimacy and life felt over our evolutionary first fifteen years was not contained in that concrete space, the big glass windows that crashed so quickly one day, the black stenciled animal heads spray painted on white, nor the old brick of the original strip where so many memories were made and lost. Our home changed dramatically one day, this Hite barn rebuilt between city towers, redesigned with clean lines and warm wood that reflects our commitment to structure, strictness, and hospitality. Any move is risky, and this project is no exception. With the calculation ingrained in my accounting-filled brain, we risked moving a couple blocks west from Boston to Boulder, from 18th to 17th, from strip mall to this iconic stand-alone structure designed practically and purposefully to enhance your coffee and community.

I had whisky with my friend, a priest in the Catholic Church, and we talked about the transubstantiation that he believes occurs in the wine and the wafer upon being blessed in the cathedral. In my skepticism we debated what that substantive transformation really is, and he explained to me that they believe the spirit of God becomes entwined within the molecular structure of the blessed sacrament, in essence making the communion a consumption of the Holy Ghost. And I believe the same has occurred at The Rookery; the spirit of so many souls have blessed this structure, transforming it from the barn that once held dairy cows and lofts of hay into The DoubleShot, a loving, loved, foundational home for our community. I know this because the night before we opened, on March 4, after a couple years of construction, of cranes and welds, of hammering and sawing, painting, and installation, I stood in this building and looked around, all alone, and my heart sank. My heart sank because all I saw was an empty building as cold as the one we’d just left. A church without a congregation. A wafer without the Spirit. And it wasn’t until the morning of March 5, on the DoubleShot’s fifteenth birthday, when people filled The Rookery and the structure was baptized with the ethos that sprouted from a coffee seed and grew into the tribe of outstanding individuals who really are the DNA of the DoubleShot. And my soul was renewed.

So at this time of Thanksgiving, I want to send this special sentiment of gratitude to you. Thank you for embracing the change. Thank you for trusting us to make healthy, quality decisions that we believe will improve our product, your experience, and the lives of so many people. The changes of the past several months have been huge, but we continue to find new ways to do better, and we will always steer in that direction. Thank you for supporting us as we all take this amazing journey through life together.

Have a safe and enjoyable Thanksgiving.

The coffee of Autumn

The moon is a blazing orb shrouded by the branches of bent, arthritic oak in the eastern sky. What an amazing spectacle it is as it rises over the treetops to illuminate the night. One of those moons I used to wish for throughout the night of an adventure race; one that freed us from the need for headlamps. The kind of moonlight that made me turn off the headlights of my car and drive by the reflection of the snow on a wintry night in Illinois when I was a foolish teenager. The wispy clouds shine white in the inky sky with pinhole stars scattered sparingly between.

I’m in the Wichita Mountains, sitting in front of a small, hot fire with the moderate chill of night and chirp of crickets surrounding me. On the three-hour drive here I was drinking our newest coffee, Sircof Venecia Honey. It’s a seriously good cup, tightly wound with pear, chocolate and honeysuckle, but today I noticed a savory nutmeg finish that lingered sweetly like a good Scotch. It’s Autumn and Thanksgiving is rapidly approaching. The season of dusk with the cold night of Winter on its heels. The past two Wednesdays, after the Wednesday Night Ride, I pedaled my bicycle home in the fading light of day. And at the crest of the bike path in Crosbie Heights, overlooking the mellow Arkansas River, above the railroad tracks with the trestle crossing water and a background of oil refinery towers and tanks, the orange light of dusk stopped me in my tracks. The receding, colorful light reflected around a curve in the river, glinting off the water, the color of the embers in my campfire. It’s really amazing to watch the sun set and the sky turn midnight blue. It feels like a miracle.

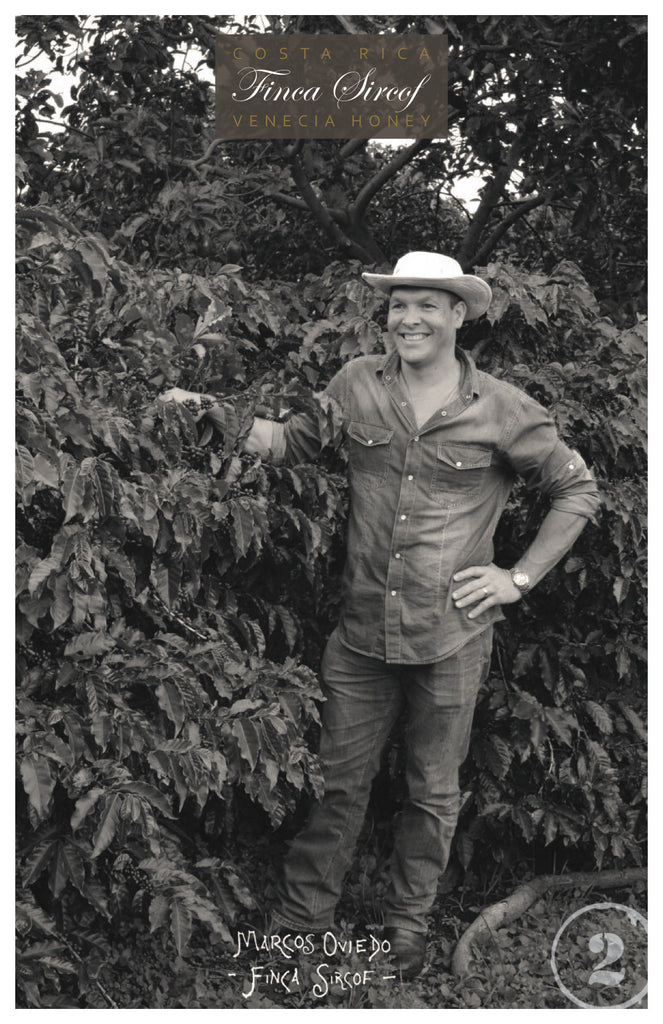

This past April I was at Finca Sircof, in the Alajuela region of Costa Rica. As I walked around the farm, visiting with Marco and Maricela Oviedo, it was apparent why this coffee is so good. The farm is small and the milling is primitive, and Marco is a meticulous farmer. His land was clean and organized. The trees were healthy and productive. And he seemed to know each individual coffee tree, having raised them all from seed, nurturing them into fully productive adults. Marco was aware of the fragrances and flowers and fruits throughout his land. He seemed more curator than farmer. But his youthful, weatherbeaten face and calloused hands showed his dedication to the work of farming. The Venecia variety of coffee is a relatively unknown tree, found only in the lands around the Alajuela region. Known for its productivity and uniformity, the variety has a surprisingly tasty profile. Marco grows this coffee, harvests it at the peak of ripeness, and processes it in a way that can be very tricky. He strips away the skins of the coffee cherries and spreads the sticky, mucilage-coated beans on the ground beneath a greenhouse arch. Dried in the sun over the course of twelve days, the coffee develops a sweetness and flavor which enhances the inherent cup of the Venecia coffee. Probably the most technically difficult type of milling, this is a process that’s easy to mess up. But Marco pulls it off spectacularly. And he’s doing it right now. Coffee production, processing, export, and import are time-intensive, so the coffee you are drinking today is the coffee Marco was making a year ago today. It’s a masterful cycle, and I hope you’ll think of his hands in the coffee as you enjoy this cup.

After I visited Marco and Maricela, I took a four hour bus ride to Arenal Volcano to run an 80km race through the rainforest. Running very long distances is one of the things that refreshes my mind and spirit and keeps me sharp and able to do what I do every day. It’s the simplicity of running and the grueling determination required that steels my resolve and enlivens a spirit of new possibilities.

This race was particularly inspirational and as I ran into the approaching night, with a flashlight on it’s last leg, I grasped a sense of ultimate freedom. Like this full moon loosing itself from the thorny grasp of the silhouetted trees to soar into the lightly veiled sky. Autumn holds that freedom. Released from the grip of Oklahoma’s oppressive summertime heat, we bask in the campfire smoke and the fragrances of the season, the chill air, the turning leaves, and the rich flavors, which are perfectly delivered in a cup of Sircof Venecia Honey.

Relationships

Oklahoma’s Wichita Mountains have long been a part of my life. My first trip there was when I was but 9 years old. My family had a sort of reunion in the picnic area at the base of Mount Scott. I remember my older cousins boulder hopping on the rocky flanks and my unsatisfied desire to join them.

My next trip there happened 14 years later. I was a fledgling rock climber and had heard great things about Elk Mountain. My naiveté about the scale and complexity of those boulder-piled mountains and the intense summer heat found me convulsing with cramps at the end of the journey.

Despite somewhat auspicious beginnings, I befriended the rock and have since summited many of the Wichita’s peaks, slept many nights in their shadows, and explored many miles on- and off-trail, looking for summits and treasures and to feel the past where I tread in the footsteps of Indians who hunted and lived and explored these same haunts. This past Summer I bushwhacked more than I hiked. I chose my own way, and I was rewarded with grand views and fantastic sightings. I walked within herds of buffalo. I spied 20 elk from one mountaintop. I found a 4-foot long antler lying among a martian-like landscape of white, twisted trees in a controlled-burn area. I stumbled upon the skeleton of an elk, its spine arched over a boulder, where coyote or lion or bobcat had feasted heartily. I even had a very rare sighting of a porcupine in the crevasses and caverns between massive rocks near the Spanish Canyon, where an outlaw Spaniard lived in a cave within Indian territory in the 1800s.

My house is in one of Tulsa’s oldest neighborhoods. It sits up on a hill near a monument for Washington Irving, who wrote about his passage through this land in “A Tour On The Prairies.” Irving traveled with a troop of Rangers exploring the territory and looking for Osage hunting parties. While encamped near my house, Irving wrote, “Just as the night set in there was a great shouting at one end of the camp, and immediately afterwards a body of young rangers came parading round the various fires bearing one of their comrades in triumph on their shoulders. He had shot an elk for the first time in his life, and it was the first animal of the kind that had been killed on this expedition.”

Just down the hill, at the base of this neighborhood, is Tulsa’s oldest park. It was sold to the city by Chauncey Owen, who inherited the land from his Creek Indian wife, Jane Wolfe. Chauncey hoped, rightly, that the creation of a park would increase the attractiveness and value of the remainder of his property in this neighborhood (á la George Kaiser). Quanah Avenue divides the park from the neighborhood, and is a main thoroughfare used by the numerous shapes and sizes of ducks and geese that call our Owen Park home. Swan Lake we are not.

Quanah Parker, the last great Comanche war chief, roamed the plains and peaks around the Wichita Mountains until his surrender and assimilation into a new culture at Fort Sill. Quanah was born in Elk Valley, where I have climbed so many boulders and slabs, to Peta Nocona, a Comanche chieftain, and Cynthia Ann Parker, who had been kidnapped as a child by a Comanche war party that massacred her family in Texas.

In 1890, Quanah built a mansion at Fort Sill and lived as the leader of the Comanche people on the reservation. His residence, called Star House, was moved off Fort Sill to Chache, Oklahoma in 1957. I went to see it last weekend, but was disappointed not to have found the house, only The Trading Post, which is owned by the man who now owns the dilapidated Star House.

If you’ve spent much time at the DoubleShot over the past couple of years, you probably met one of our regular customers, Greg Peterson. Greg is one of those charismatic guys who has a genuine smile and a way of making you feel like he thinks you are better than you really are. If he told you his career is as a college football coach, you wouldn’t have been surprised; tall and imposing with an athletic build, he looks the part. His most recent stint was as the offensive coordinator at the University of Tulsa during their successful seasons. In his time at the DoubleShot he cycled a lot and conversed warmheartedly, and he exuded a desire to coach again. Unfortunately for us, but fortunately for him, he was hired as a wide receiver coach at Eastern Illinois University and moved to Charleston, Illinois (not far from where Cynthia Ann Parker was born).

Before he moved, Greg connected me with a friend of his, Jon Jost. I emailed Jon a couple of times and found that he was from Nebraska, and is married to a Costa Rican woman (á la Peta Nocona). They had recently moved to Costa Rica and were farming coffee. I met Jon at the convention of the Specialty Coffee Association of America in April and we talked about trail running and coffee, both of which flourish in the Cordillera de Talamanca, the foothills of which Jon’s farm is perched.

Jon and his wife, Marianella have successfully mined the channels and found brokers and roasters who are eager buyers for all of their coffee. They are also opening up these pathways for their neighbors. At SCAA, Jon gave me two coffee samples, one from his farm, which was already sold out, and the other from a farm called Finca Sircof. I sample roasted these coffees and put them on the cupping table with coffees from Africa and Brazil. This Sircof Venecia Honey really separated itself from the others with aromas of berry and a sweet, smooth taste.

Finca Sircof is owned by Marcos Oviedo. His farm is near the farm of Jon Jost. Marcos has spent the last few years improving the quality of his coffee, building a micro-mill on his property, and experimenting with different processing methods. The Venecia variety is a new type of coffee for us, and I really like it. A mutation of the Caturra variety, it retains the solid structure of the Caturra, but benefits from slower ripening to add density and complexity.

Marcos processed this coffee using the Red Honey method: after picking only ripe coffee cherries, the skins were stripped off and the beans dried with the fruit pulp still intact. This method results in a very tasty coffee with sweetness and smooth, slightly fruity vanilla aromas.

This is the coffee we are drinking to celebrate Thanksgiving. To celebrate relationships. Washington Irving drank coffee near my house, in the vicinity of the future Quanah Avenue. Quanah Parker drank coffee in my weekend home in the Wichita Mountains. And thanks to Greg Peterson, Jon Jost, and Marcos Oviedo, we will drink delicious coffee with our families in our homes and at the DoubleShot this holiday season.

Read more about this amazing coffee and buy a pound on the DoubleShot website. We are selling the coffee in one-pound commemorative black bags with a card affixed bearing a photograph of Marcos and information about the coffee. Happy Thanksgiving.

El Erizo

The pin-pricks of coffee’s tiny guardian mosquitos remind me that in the dense, diminutive forest of it’s mountainsides I am a guest, and its harvesters are armored with long sleeves and t-shirts around their heads appearing like so many muslim women, faces protruding from a habit of Hanes. Like soldiers waiting to be called upon to defend the coffee. I skirt amongst outstretched branches, a turnstile of spindly sticks and corrugated leaves, the smallest of which have a thick, rubbery texture that seem to transmit to me the health and wellbeing of the plant when I caress its surfaces as one in love.

They ask me why I touch the leaves that way.

I like to feel them.

They ask if I have children.

The coffee trees are my children.

They say I have a lot of children.

I love coffee. It’s fruit is a life-force I pluck with earnestness and purpose. I select the ripe cherries intently and pop them in my mouth for a chew on the fibrous skin and I tuck the twin seeds in my cheek to taste its slimy fructose-covered shell, like a chipmunk storing up for winter. Or I pop them in my blue jeans pocket, filling with seeds of the Maragogipe or cherry of the Yellow Caturra. Amongst millions of trees, each bearing over a thousand cherries, they ask why I put several in my pockets.

These are magical beans.

They think I am crazy.

I look into the eyes of the coffee picker and I ask her name and she says Claudia. She tells me she is thirty years old. I ask her how long she has been picking coffee and she tells me, “All of my life.” I tell her she is beautiful.

I examine the strong yet delicate hands of the farmer whose skin is creased with a lifeline that parallels the family tree of his coffee. The sticky stains of coffee juice show upon his clothes and the knowing way he manages the harvest.

And the processing of our coffee crisscrosses cultures and interweaves several centuries of rudimentary practices. I ask, when was the contemporary machine invented that removes the skins of the cherry and which is so pervasive across the coffee washing stations throughout the world. They tell me around 1650, when the Dutch took coffee from the arid mountains of Yemen and planted it in the island rainforests of Indonesia. An enduring method and machine, invented of necessity by interlopers.

The history of the process is the history of the cup. From the port of Mocha in Yemen to Java, Indonesia, the world’s oldest blend was born. The traditional dry process of Yemen and Ethiopia yields distinctly different flavors than the wet process that enabled coffee cultivation to be spread throughout the world. The colors and fragrances of these unroasted, processed coffees trickle through my fingers and into my nose as I sift through my burlap meditation garden.

Coffee is the history of bondage and freedom. Of the slavery once predominant in plantations of French and English and Dutch colonies and of the uprising of the suppressed. In roasting coffee, as the color changes from green to straw to tan and the aromas evolve, the coffee is absorbing the heat from its environment in the roasting drum. But at a certain time and temperature in the cycle, our coffee begins to rise up exothermically, audibly snapping and releasing energy in a vibrant celebration of life and liberty.

I snoop around a coffee mill and I feel the tears in the plastic mesh flooring of a raised bed built for a special project of naturals just for me. A European roaster inquires curiously but conservatively, and I ask if he is interested in the natural.

NO, he snaps.

They tell me someday my palate will mature and I won’t like those coffees any more.

I think, maybe my respect for mankind will mature someday and I won’t like freedom or diversity any more. And I’ll take my elite cupping spoon to Costa Rica to subdue the coffees under one standard profile. Should we not question the status quo and ride away in container ships back to San Francisco, our bland, unwavering coffees barely allowed to reach that exothermic crack before being put down, hushed.

In Costa Rica, coffee transformed from ornamental garden plant into the chief export in the mid-1800s.

Seeing a weakness in the recently-independent states of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, a privateer named William Walker gathered a small army and set sail from San Francisco to make slave states of those emerging countries. His success in Nicaragua was quelled by an uprising of meager but impassioned farmers from the rolling countryside of northern Costa Rica. The impromptu civil defense drove the pirates back into Nicaragua, trapped in a hostel in the town of Rivas. One young farm boy-turned-drummer boy from the town of Alajuela charged the hostel and set fire to its foundations, laying waste to the fortress and sending Walker and his cohorts fleeing to Honduras where they were summarily executed by firing squad.

Inspired by the young Alajuelan, Juan Santamaria, whose nickname was El Erizo, we pay homage to his bravery and forthrightness. Our first special coffee for this holiday season, El Erizo, is a departure from the pent-up standards espoused by San Franciscans, where they roast only washed coffees and only until they begin to hear the coffee cry out, whereas the voices of the past make them nervous and the emerging uniqueness of flavors, of freedom, are dismissed, enslaved. And we burn down those walls and release the sweetness and amazing flavors within the coffee, within the farm boy who planted and picked the coffee. With Thanksgiving we offer this rare treat - a Honey Process from Alajuela that tastes, in all my experience, like a beautiful natural.

They ask me why I love the coffee.

It personifies freedom.

Yellow

Yellow has never been my favorite color. I look around and see it non-intrusively accenting the room, a powerful, though scant slice of the color spectrum. Most of life is muted earth-tones and yellow is celestial. A yellow flower in a field of green and brown is a paragon of uniqueness, leadership, or outstanding beauty. Our yellow star provides warmth and happiness, though in extremes, misery. And the yellow in our urban society warns us to be cautious. Yellow, in moderation, is fantastic.

As an incautious kid, I roamed the woods and fields, first of the corn and soy prairies of Illinois, and then of the cross timbers in southern Oklahoma. Days and nights were spent building tree forts, fishing for mud cats, exploring every hill and dale, and of course playing "war" with my cousins. Like the kids of "Lord of the Flies," our free time was spent dividing and conquering one another. On my Uncle's 80-acre pastureland were two ponds, sparse woods, a hay barn, and a pair of combines - an immense battlefield with adequate relief and cover.

On a sunny Summer Sunday, after lunch all the boys of my extended (and extensive) family grabbed a broomstick or some other janitorial representation of a weapon and we split into 2 groups. We fled in separate directions into the wilds, avoiding cows and their excrement. Our troop ranged the ponds and pastures looking for the enemy, with occasional contact and shouts of "BANG BANG BANG! I GOT YOU!" Invariably if one cousin got the jump on another cousin, the surprise attack would win out and no matter how much negotiation, the surprised party would succumb to their slow reactions and relent to lie on the ground, close their eyes, and count to 100 while the ambush team scampered off looking for another tactical position.

My team crossed a dike containing one end of a cow pond, and descended the grassy slope where we climbed over a huge tree which had died and fallen like Gulliver on Lilliput. I, being the younger of my cousins, hung back and waited for each one to crest the horizontal trunk and leap to the ground. When my turn came, I stepped down onto a lower part of the trunk and suddenly, having fallen through rotten wood, found myself engulfed in a nest of angry, swarming, stinging yellow jackets. My older cousin pulled me out and carried me back to the house, as, from shock or venom, I couldn't stand.*

Way back in the hills, up a long dirt road is another farm called La Pastora. This farm, far from the rolling plains of Oklahoma, has steep fields upon the mountainsides of Costa Rica's Tarrazu, planted not in hay and cattle, but short, spindly coffee trees. The owner of La Pastora, Minor Esquival Picado, is the epitome of a happy, paradisiacal homeowner. You'd almost think his every-present grin was the product of having seen our lifestyle and then reverting back to his leisurely customs. But I suspect Minor has never been far from home.

Unusually, Minor built a small but pristine mill out of concrete and a mishmash of ceramic tile remnants, many broken into pieces. He uses this mill to process small lots of coffee that he thinks will be special and worth more than the regular coffee he sells to the regional mill in San Marcos. After Minor built his micro- wet mill, he began experimenting with Naturals and Honey coffees. Laying the coffee to dry in the sun on raised, African-style beds, which Minor built on the flat, dry ground between the mill and storage barn, he produced three different styles of Honey coffee. They are called Black Honey, Yellow Honey, and White Honey, derived from the color of each bean as it dries in the sun. Had Goldilocks the privilege of sampling the Three Bears' coffee stash, I don't think she would've done a better job than I of picking out the one that is just right.

I have two pictures hanging in my house that mean something extra-special to me. One, a bluish-hued lithograph of "Lone Wolf" by Alfred Kowalski, which hung in the back room of my Grandpa's house above an old sewing machine. In it, the foreground is of a wolf, his tracks visible in the snow, looking down a precipitous hillside onto a house - a very small village, maybe - what could be, except for the snow, Minor's farm. The other picture is a yellowed print of a painting of James Earle Frasier's "End of the Trail." This picture I got from my dad, who acquired it when he was a kid. Only recently did I realize that both of these pictures have the same origin. They were printed at a place in Chicago called Borin Mfg Co, both in 1925. They're both in the original frames. Borin printed dozens of paintings, and it appears that they maybe avoided paying royalties to the original artists by printing them all backward. So I have two backward prints, one of a famous painting that seems to correspond to my M.O., and the other of a famous statue which now resides, forward-facing, at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. The story of Frasier's statue is a fascinating one, and it just so happens that Mark Brown wrote about it in the current issue of This Land magazine. I stumbled into this history from a coin my dad gave me: the Buffalo Nickel. It's a keepsake. An antique. And originally designed and modeled by the same artist, James Earle Frasier, as a tribute to the American West.

I learned something at La Pastora that I probably could've learned at my Uncle's when I was carried back to my mom at HQ, a wounded soldier. The skin of the coffee cherry, much like the wood of a hollow tree, is a protective coating. When left intact, nature can take its course, the coffee cherries can dry into a sweet, fruity Natural; and the yellow jackets can work as a biological pest control by hunting other pests, reproduce into a seasonal colony of a few thousand, and no one would be the wiser. But once that fragile shell is punctured, what's inside is volatile. Honey Process coffees involve removing the protective skin of the cherry and exposing the sticky pulp to environmental forces of oxygen, bacteria, and yeast. What Minor figured out is that falling into a nest of yellow jackets can leave a bad taste in your mouth. He removed some of the pulp from the coffee beans. Not all of it, but just the right amount. And what he came up with is a smooth, delicious, sweet-tasting coffee that has all the fullness of flavor I look for in a special Thanksgiving offering.

La Pastora Yellow Honey, though grown in Costa Rica, came to fulfill its purpose here in Oklahoma, in my roaster, and ultimately in your cup. Frasier's Indian found its end of the trail here too, but you'll have to read about that while drinking the Yellow.

Happy Thanksgiving, Y'all.

READ ABOUT THE BOX SET AND BUY LA PASTORA YELLOW HONEY HERE.

Buy the issue of This Land with Mark Brown's story of The End of the Trail here.

* The yellow jacket incident could explain how I acquired super powers.

Kemgin

Well, the holidays are upon us once again. And as usual, we have pulled out all the stops to bring you some amazing coffees during your holiday celebrations. This Wednesday night marks the beginning of Hanukkah, and Thursday is Thanksgiving, so right now is the opportune moment to purchase the first of these brilliant coffees.

Kemgin is a very high-end coffee from Ethiopia that we procured through Ninety Plus, who have brought us so many exquisite coffees throughout the years. We offered the Kemgin a couple of years ago, and it was a big hit then, so we've brought it back for another go-around. This is a coffee that has been celebrated by coffee reviewers and professional tasters, as well as winning top coffee at the Good Food Awards.

Because of the region where it is grown, the care with which it is picked, and the clean processing and sorting of Kemgin, it achieves some of the flavors that make coffees stand out as the best coffees in the world. Aromas of jasmine and lemon lead off, and as you taste the coffee, nuances of black tea and orange excite your palate, with a long, silky finish with highlights of pine. Perfect for the holiday season.

Because we care about your coffee experiences at home, we came up with two food pairings we think accentuate the coffee in different ways. Obviously you'll want to drink Kemgin by itself, but having just the right thing to go with it for breakfast and dessert makes the coffee all the more pleasurable. Follow these recipes for our Cranberry-Orange Muffins and Blackberry Cobbler.

Cranberry Orange Muffins (courtesy of our baker, Kristin Hoffman)

1 orange (including peel), quartered with seeds removed

1/2 Cup orange juice (juice of 1 orange)

1 egg

1/2 Cup butter, melted

1-3/4 Cup all-purpose flour

3/4 Cup white sugar

1 tsp baking soda

1 tsp baking powder

1/4 tsp salt

2/3 Cup dried or 1 Cup frozen cranberries

Preheat oven to 400ºF and prepare 12 muffin cups with spray or paper liners. Puree orange quarters and orange juice in a food processor or blender. Add egg and melted butter to orange puree and blend until smooth. Sift dry ingredients together in a medium-sized bowl, then add orange mixture and combine. Stir in cranberries. Fill muffin cups with batter. Bake 20 minutes.

These tend to bring out the black tea flavors in the Kemgin, as well as some soft vanilla flavors that really make this pairing meld together.

Blackberry Cobbler (courtesy of my mom, Millie Franklin)

3 Cups frozen blackberries (do not thaw)

1 large pear, halved, cored, thinly sliced

2/3 Cup sugar

3 T orange juice

2 tsp orange zest

1/2 tsp ground cinnamon

Gently toss all ingredients together. Pour into buttered pan.

1 Cup flour

1 Cup sugar

Dash salt

1 Stick butter

Vanilla & Almond extracts (to taste)

Mix sugar, flour, salt, and sugar in food processor with butter until crumbly. Add vanilla and almond extracts and pulse again. Pour over fruit and bake 350 degrees until brown and bubbly (45-50 minutes).

The pears in this cobbler really smooth out the acidity in the blackberries, and the whole thing brings out the citrusy aspect of the Kemgin, and the cinnamon really carries forward through the coffee to make for a unified experience.

Both of these recipes are just unbelievably good, and I highly suggest you give them both a try while you have Kemgin in hand. And it's not going to last long, so buy some today!